Some documents shed light on the difficulties of producing reliable biographies of men mobilised during the First World War. Sometimes it’s an administrative document, other times it’s a testimonial. Here, it is a photograph that forces us to put the other sources into perspective, while at the same time complementing them in unexpected ways.

The documents from Européana provide valuable information, without emphasising a rarely visible element.

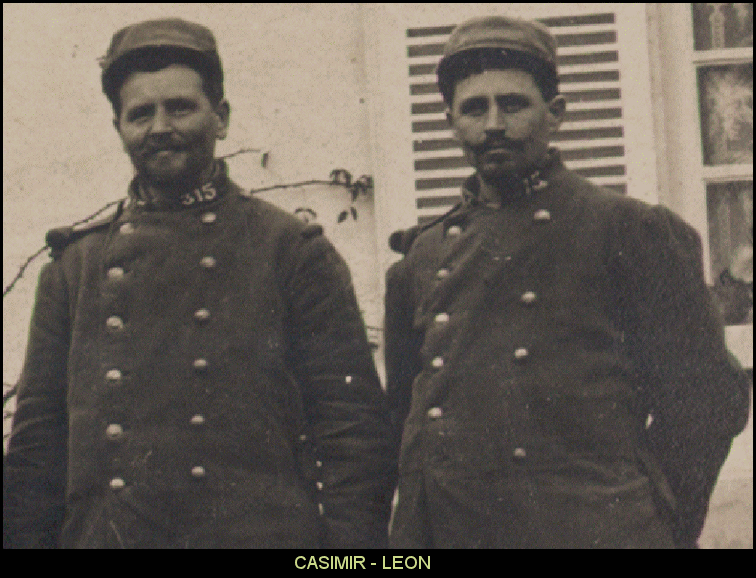

- Casimir and Léon Derouin

Some documents on these two brothers have been digitised and put online on the Européana website following the Great Collection of 2014. Without these documents, what would we know about these two brothers, Casimir and Léon Derouin? Essentially what their service records tell us, which is not much.

Both attended the local school in Rouperroux, Sarthe, where they were born. Their school grade was 3. The younger Casimir was ‘trained’ in terms of his military preparation. He was also four centimetres taller at six foot eight than Léon. Léon, the eldest, had health problems, going from medical commission to medical commission with a suspicion of tuberculosis. Initially posted to the 103rd Infantry Regiment, he then spent a few months with the 115th Infantry Regiment in Mamers before being discharged. His brother spent two years with the 146th Infantry Regiment.

Only the younger brother obtained his certificate of good conduct, as Léon had spent too little time in the army to have to justify it. They resumed their farming activities, Casimir at Rouperroux, Léon at Saint-Cosme from 1905.

In 1906, Léon once again went before a medical commission and was definitively recognised as fit for armed service. Now a reservist, he was obliged to take part in training exercises.

Like all reservists, the two brothers were posted to a regiment close to their home, in this case the 115th RI in Mamers. Léon did two periods, one for manoeuvres in autumn 1908, the other in March-April 1911. His brother served only one tour, during the autumn manoeuvres of 1911, as the second did not take place because of the war.

It is not clear how each of them fared in the conflict. Here is what we can deduce from the few entries on their service cards. Léon was called up on 11 August 1914 to the 115th Infantry Regiment depot. He trained there until his departure for the front on 20 September: he was one of the men who remained at the depot and were then sent to reinforce the regiments weakened by the fighting in August and September. He remained at the front continuously until he was evacuated due to illness on 6th October 1915. He did not return until April 1916, and took part in his regiment’s fighting at Verdun, from where he returned with the Croix de Guerre and the following commendation: ‘Brave and courageous liaison officer from 17th to 27th July 1916, demonstrated excellent qualities in transmitting orders in open terrain subject to incessant shelling’.

Evacuated again for illness in April 1917, he did not return to the front until his discharge on 27 February 1919.

Casimir, who was younger, was mobilised on 4 August 1914, also with the 115th Infantry Regiment. His service record tells us nothing about his career until 6 September 1916, when he was killed at Verdun, in the Fleury-devant-Douaumont sector.

As we can see, there are few certainties. Above all, two family photographs will enable us to refine these elements, starting with his posting.

- 115th RI or 315th RI?

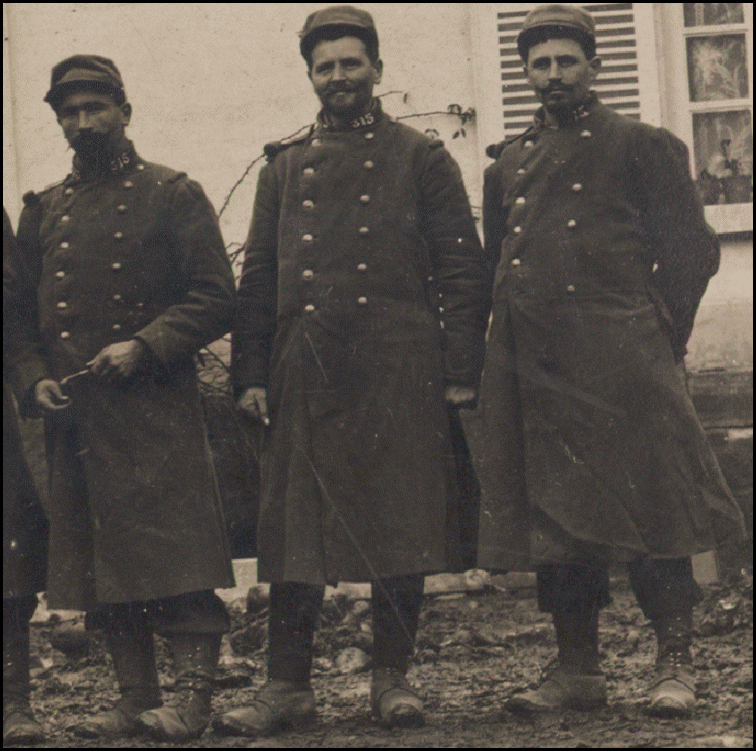

The photographs available all show, without a shadow of a doubt, that these two men were not in the 115th RI, but in the 315th RI, the soldiers having had the good idea of whitewashing their regimental numbers with chalk to make them clearly visible.

However, this was not an error in the registration form: as the 315th RI was a reserve regiment, its personnel were still managed by the depot of the active regiment, the 115th RI. For the military authorities, it was not useful to mention the precise regiment in the registration card, as they knew who had managed them.

The photographs were not essential in reaching this conclusion. Casimir was killed at Verdun in September 1916. His ‘Mémoire des hommes’ record clearly shows that he belonged to the 315th RI. What’s more, the 115th RI was in Champagne at the time. All the photographs, including two that can be dated to late 1915-early 1916, show him in the uniform of the 315th Infantry Regiment, as we shall soon see.

For Léon, things are more complicated. Surprisingly, we have no other photographs of him. His citation, for actions in July 1916, does not correspond to the 315th RI but to the 115th! Although it is not possible to give a chronology, it seems that Léon passed through the 115th RI, probably after his return from illness in April 1916 until his departure from the front in April 1917.

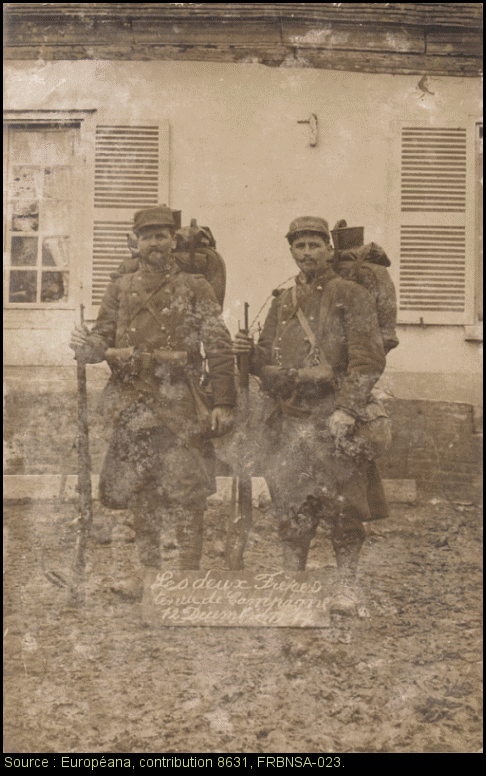

- ‘Two brothers’ on the campaign trail

The photographer had the good idea of keeping his slate so that the soldiers could add a few identifying details.

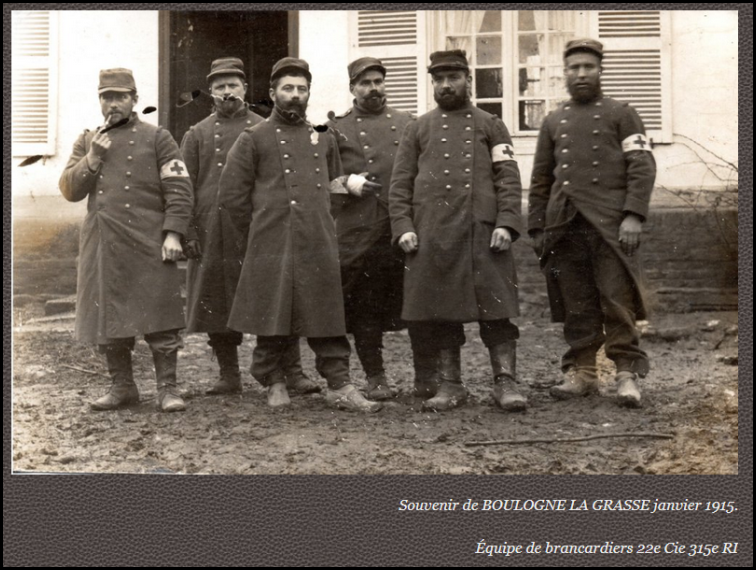

The first photograph shows a group of men in front of a house. The slate reads ‘1st Squad’.

If we don’t know the company, we can also tell that they are soldiers of the 315th RI and the words ‘1st squad’ tell us that this group is not there by chance. These men made up the smallest group of French units, the squad. Two squads make a platoon, two platoons a section, four sections a company.

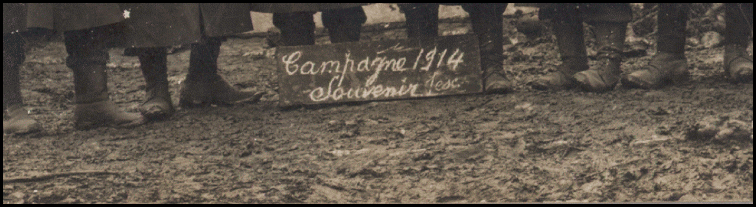

Everything suggests that the men were resting on a farm at the end of 1914. The courtyard is muddy and the words ‘1914 campaign’ are typical of inscriptions from the beginning of the war.

It is certain that the photograph was not taken at the depot because the uniforms are too uniform and the men are all wearing kepi caps, which is not usual at the depot. One man had replaced his gaiters with calf pads. Another no longer had all the buttons on his capote.

The second photograph was taken in the same place.

This means not only on the same farm, but also in front of the same wall. There are some significant details:

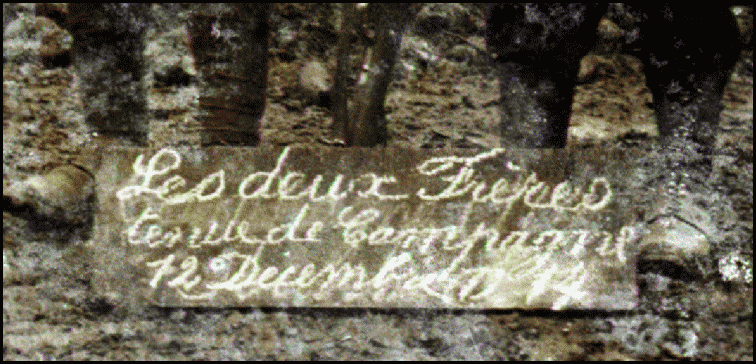

The slate is very interesting because it gives us several extremely valuable elements.

Firstly, a date: ‘12 December 1914’. This date explains the mud on the ground and means that the regiment was in the Dancourt-Popincourt sector. Unfortunately, as the precise billets are not known, it is difficult to identify the location for the moment, as there is no JMO for this regiment and the history is only a few pages long for the whole conflict.

Secondly, the two brothers appear in the photograph. Without this indication and in the absence of any other information, such a photograph could have lost this information.

The lack of precise identification will not lead to an – often – futile search for ‘who’s who’. Thanks to the other photographs available on Européana, it is easy to identify Casimir.

So we have :

The last important point is that by identifying the brothers in the second photograph, we can see that they are both present in the first! So these two brothers were probably in the same squad. I added ‘probably’ because, once again, if everything suggests that this is the case, we can’t rule out the possibility that one brother joined the other for the shot. However, I doubt it because in that case, would the mention of the squad have been left in?

If there was any doubt about identification, the veteran’s card with his photograph confirms what we know.

- Two brothers in the same squad?

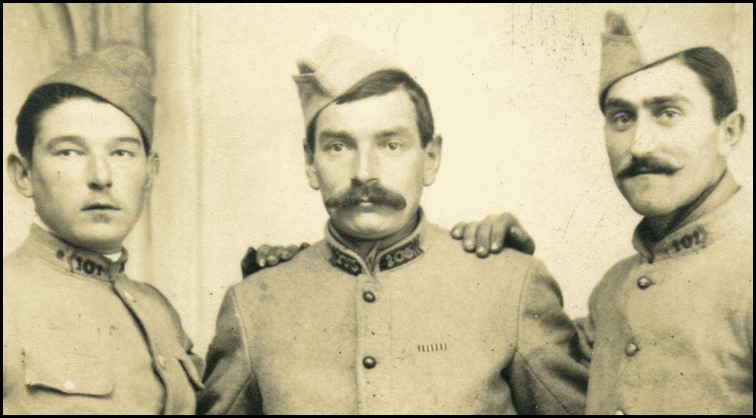

The presence of two brothers in a regiment is not unusual. Thanks to the Internet, there are many examples of such situations. I have already mentioned on this site the Jollivet brothers, two of whom were posted at the same time to the 101st RI.

Several discussions on the Pages 14-18 Forum with specific examples have been created around this theme. The easiest way is to list the brothers who died in combat (sometimes on the same day). Vincent Lecalvez has done this very well for the 28th RI: twice brothers were killed in the same place by a shell : http://vlecalvez.free.fr/Freres_du_28eRI/freres_28e%20RI.html. On the 119th Infantry Regiment website, you can read a beautiful account by one of the Létondot brothers.

http://119ri.pagesperso-orange.fr/Fantassins/Letondot/Letondot%20partie%204.html

On the 149th Infantry Regiment website, you can read about the tragic fate of the Delort brothers, who had just been posted to the 12th Company in May 1915: http://amphitrite33.canalblog.com/archives/2015/06/17/32213591.html

It is hard to say whether these men were in the same squad, the same company, the same battalion. The case of the Létondot brothers and those mentioned for the 28th RI seem to indicate that the men belonged to the same group, since they died at the same time in the same place (a shelter, a cellar) or were close to each other when one of them died.

There are more general examples that show the reality of this situation, particularly at the start of the conflict. Stéphan Agosto, for example, already had more than thirty siblings in the 74th RI.

The reasons for these postings are not difficult to establish, particularly in cases documented by correspondence or testimony. The simplest reason is that the two brothers, who were reservists, were posted to the same regiment because they lived in the same place. This explains a large proportion of the cases at the time of mobilisation. It should be added that, before the war, it had been legally possible to reunite brothers in the same unit for active service, at least since 1910.

‘Art. 6 – Assignment of conscripts with a brother in the armed forces.

Brothers forming part of the same call-up and all brothers of servicemen already attached to the service as conscripts or enlisted men, with the exception of brothers of re-enlisted servicemen, commissioned servicemen or officers, must, if they so request and if they are physically fit, be placed in the same regiment or in the regiment in which their brother is already serving at the time of their call-up, whatever the reason for which the first brother was assigned to a particular corps. It is understood, however, that these provisions do not apply to the brothers of men serving in the test corps, nor to young soldiers who have incurred convictions or who have not produced in good time the certificate of good conduct under the conditions indicated in article 5 for married men and breadwinners. If the younger of the two brothers (or the last to be called up) is not physically fit to serve in the same corps as the elder (or the first to be called up), this young soldier will be assigned to another corps stationed in the same garrison, if this garrison includes troops from other arms (including sections).

The interested parties must send their request to the commander of the recruitment office to which they belong, within fifteen days of their appearance before the review board.’Instruction relative à l’affectation des jeunes soldats, à l’appel et à la libération des classes, 16 April 1910.

What seems more complicated and a bit more random is the subsequent posting to the same regiment as a brother who is already there. This could be made easier by voluntary enlistment. I don’t have any examples of brothers but such was the case of a father who came to find his son in the same regiment (JMO of the 4th RMZT, 20 June 1915-9 January 1917, 26 N 855/9, page 38): the text of his citation tells us ‘Aged 52, enlisted for the duration of the war in a unit where one of his sons was serving’. His enlistment made things easier.

Reading the testimonies shows that officers had real power when it came to assigning men to a company. Here is what Maxime Leydet wrote following the arrival of the class of 1914 soldiers in November 1914:

‘These days, we have received 40 men per company to fill, for the second time, the gaps created in our ranks. Among the latest arrivals (…) Boeuf Firmin, who not only belongs to my company, but whom I was able to get to join my squad by begging the captain (…)’, pages 277-278 of Nicolas Balique’s book, L’adieu aux pays, correspondance de guerre de quatre soldats bas-alpins.‘

In another example, dated 5 December 1915, Cyrille Ducruy wrote:

‘I’ll tell you that yesterday I changed companies, I went back to the 3rd with Démure [a friend from the country], we’re both in the same squad (…) It was almost 18 days ago that I asked the colonel to change with a man from the 3rd company who had his brother-in-law in the 5th. I wasn’t counting on it yesterday when the reply arrived’.

Extract from Dargère Christophe, Si ça vient à durer tout l’été… Lettres de Cyrille Ducruy, soldat écochois dans la tourmente 14-18. L’Harmattan, Histoire de la défense collection, Paris, 2010. Page 111.

It was therefore possible to ask to be reunited with a family member, but there was no guarantee that you would get what you wanted. Despite the assertions of an article in the newspaper La Voix du Nord on 14 November 2010, no standard text (instruction, directive, etc.) has been found prohibiting these postings or calling into question the 1910 directive.

There are also accounts of soldiers arriving as reinforcements and being separated from one another, regardless of the ties that bound them together. We can therefore imagine that the situation of the Derouin brothers was, if not facilitated, at least authorised following a request and not just the result of chance. But did this happen when Léon arrived in September? Or later? In the absence of any other source, it’s strictly impossible to say. What is certain is that such a grouping on a photograph taken at the front is not very common and this aspect deserved to be highlighted.

- Conclusion

While photographs of brothers during the war are not uncommon, those showing two brothers in the same squad are less common. It illustrates this situation, which is sometimes mentioned in a testimonial, and exceptionally in a few biographies showing the death of two brothers on the same day, sometimes even within the same regiment.

It is difficult to quantify this phenomenon, which must have been more common at the start of the conflict: in the rush to leave in August, it seems to have been fairly straightforward to be posted to the same company as your brother. Once again, photographs illustrating this phenomenon are even rarer.

Comparing sources, while it helps to refine the story, does not provide all the keys. Consultation of Léon’s veteran’s card file would have revealed more about his time with the 115th RI. However, the letter D was not kept by the AD72. This source is therefore lost here.

- Location found

Sébastien from the 115th-315th RI and 27th RIT website contacted me to tell me that these two photographs were taken in Boulogne-la-Grasse. This commune lies to the south-east of the sector in which the 315th RI was on the line at the time.

Source: https://115-315-27-ri-rit.go.yj.fr/page-14.html

Two photographs posted on its website show the same building.

It is unlikely that we will be able to find the building again, as the commune was at the heart of heavy fighting in 1918.

- Acknowledgements

To Sébastien of the 115th-315th RI and 27th RIT website for his help in locating the photographs.

- Sources :

Européana, contribution de Jean-Paul Hauroigne, FRBNSA-023 Léon Pioger et Casimir Derouin

Lien direct vers la contribution : http://www.europeana1914-1918.eu/fr/contributions/8631

Lieutenant Boumier, Notice historique : le 315e Régiment d’Infanterie (dans la Grande guerre). Mamers, Imprimerie Alfred Chevalet, 1920.

Accès direct sur Gallica : http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k8598630

A la date de publication, aucun JMO du 115e RI et du 315e RI n’tait disponible au SHD.

Archives départementales de la Sarthe :

Fiche matricule de Léon Paul Derouin, classe 1901, Bureau de recrutement de Mamers, matricule 444. 1 R 1121.

Fiche matricule de Casimir Théophile Derouin, classe 1905, bureau de recrutement de Mamers, matricule 1059. 1 R 1159.

3 R 282 – Carte d’ancien combattant ; lettre D.

Deux ouvrages :

Balique Nicolas, L’adieu aux pays, correspondance de guerre de quatre soldats bas-alpins, précédée de Barles et les Barlatans dans la Grande Guerre, Les Baux-de-Provence, Jean-Marie Desbois éditeur, 2017. 374 pages.

Dargère Christophe, Si ça vient à durer tout l’été… Lettres de Cyrille Ducruy, soldat écochois dans la tourmente 14-18. L’Harmattan, collection Histoire de la défense, Paris, 2010. 320 pages.